Arunachal Pradesh: Retracing a century-old biodiversity in Siang Valley

A recent expedition by researchers and filmmakers into Siang Valley in Arunachal Pradesh yielded startling results, including the identification of several species new to science. The Siang river basin hosts 12 different types of forests, with a diversity of habitats that fosters rich biodiversity. The disappearance of habitats, in the form of deforestation and development, are among the biggest threats to biodiversity, conservationists say. Mongabay India writer Simrin Sirur reports

On July 16, 1912, the British Army published a notification announcing the success of its expedition into the heart of present-day Arunachal Pradesh. The upper reaches of the region had been a fortress for colonial forces until then, and the completion of the exercise was announced with much celebration.

“Although it proved impossible to explore the valley of the Dihang (present-day Siang Valley), where it breaks through the main mountain range on the confines of Thibet… in spite of great physical difficulties the main objects of the expedition have been accomplished,” the notification reads.

The expedition was a punitive mission prompted by the murder of a British officer, Noel Williamson, by the tribes living in the Siang valley, referred to as the “Abors” (translating to “unruly”).

Williamson arrived in the village of Komsing expecting a night’s stay but was killed for humiliating the village head on another occasion.

To avenge Williamson’s death, British forces decided to invade the valley with two objectives in mind: to gather as much information about the region as possible, and to “punish” those culpable in his murder.

An almost-forgotten legacy of this brutal mission was an unusual catalogue of animals, plants, insects, and birds found in the valley. Little was known about the catalogue, which surfaced decades later while filmmaker Sandesh Kadur was researching for his book, Himalaya: Mountains of Life.

“I found that many species were named and discovered around 1911 and 1913, and I thought, what was going on a hundred years ago?” he told Mongabay India. “I started to dig deeper and then I found this huge 1,000-page report, and I thought to myself ‘wow, this is fascinating’.”

The report was a scientific gold mine. Led by marine biologist Stanley Kemp, the scientific component of the expedition discovered 14 new genera in the Siang valley. The findings described 244 amphibians, birds, insects and one of the world’s oldest living fossils – a velvet worm called the onychophora. The Wildlife Institute of India called this expedition “one of the most comprehensive one-time biological, geographical and anthropological documentations ever conducted for any particular region in India.”

Among the findings of a 1912 British Army expedition in Siang valley, Arunachal Pradesh, was one of the world’s oldest living fossils, a velvet worm called the onychophora. Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

Among the findings of a 1912 British Army expedition in Siang valley, Arunachal Pradesh, was one of the world’s oldest living fossils, a velvet worm called the onychophora. Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

Even more remarkable is that, over a century later, several species from Kemp’s survey can still be found in the state, according to Kadur. Beginning in 2022, researchers from the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) collaborated with National Geographic and Kadur’s film production company, Felis Creations, and retraced the route of the 1912 expedition, venturing deeper into the valley and making an even wider record of species than before.

A century after the British left the Siang valley, it remains a sanctuary. On the horizon, however, a large dam project and other changes in land use threaten to alter the landscape forever.

The Siang valley

The Siang river, upstream from Assam where it becomes the Brahmaputra, served as the compass for both expeditions. It is the biggest of Arunachal Pradesh’s seven major rivers and flows freely through its entire 293.9-kilometre stretch. The river was a significant migratory route for the Adi tribe (called the Abors by the British), who descended from Tibet generations ago and settled along the river valley.

The Siang river in Arunachal Pradesh, which becomes the Brahmaputra in Assam, served as the compass for both the British and Kadur’s expeditions that took place a century apart. Image by Sandesh Kadur/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

The Siang river in Arunachal Pradesh, which becomes the Brahmaputra in Assam, served as the compass for both the British and Kadur’s expeditions that took place a century apart. Image by Sandesh Kadur/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

“Unlike other places in northeast India, the British were relatively absent in Arunachal Pradesh. Apart from the Abor expedition, there’s been virtually no sustained biodiversity assessments at all in this region,” said Sanjay Sondhi, a naturalist and founder of conservation NGO Titli Trust. He contributed to the new expedition’s findings on moths and butterflies.

The 2022 expedition into the Siang was not only an opportunity to reclaim colonial history, but also to make up for all the lost time in which systematic biodiversity research remained absent. The Siang river system is particularly interesting. The river traverses elevations ranging from 100 metres to 5,800 metres and the river basin hosts 12 different types of forests, including tropical semi-evergreen forests, alpine scrub forests, wet temperate forests and alpine pastures.

It’s because of this diversity of habitats that the Siang valley fosters rich biodiversity. Over several trips made between 2022 and 2024, the latest expedition recorded a staggering number of species – more than 1,500 – over an expanse covering the Upper Siang, Siang, and East Siang districts. These species included mammals, reptiles, birds, plants, insects, molluscs, and fish that were recorded by a team of 25 researchers, camera people, and field assistants.

Much of the research from the expedition is yet to be published, but studies that have emerged so far reveal new facts about species behaviour, habitats, and ecosystem services provided by the Siang river. Take, for example, the Paraparatrechina neela – a tiny, two-millimetre long ant found in a tree trunk hole, whose exoskeleton shines a brilliant electric blue. Metallic blue ants are a rarity anywhere in the world, and this unique physical appearance is likely an evolutionary trait to ward off prey. The expedition also yielded discoveries of species new to science, such as four new species of the Darwin wasp subfamily (Microleptinae).

An insect of the order Dermaptera. Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

An insect of the order Dermaptera. Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

A dung beetle. Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

A dung beetle. Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

But among the more remarkable findings is the rediscovery of the velvet worm, the onychophora. “This ancient species goes back 170 million years, and it’s not known from anywhere else in India except in this tiny corner,” said Kadur, adding, “It connects India to the rest of the world, biologically and biogeographically, since it was part of the ancient Pangaea. And what’s amazing is it hasn’t really evolved much since that time.”

The team also found evidence of the Siang river as a migratory corridor for birds like the common crane, never seen before to be travelling across the river in large hoards of 300 individuals. “We mostly recorded the return journeys of the common crane, which happens when they are going back to the northern Arctic Circle. These birds were never reported from the Siang valley before, and it establishes the Siang valley as an important migratory corridor,” said Rajkamal Goswami, Fellow in Residence at ATREE’s Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation. Goswami was part of the expedition team that focussed on how human interactions shaped biodiversity in the Valley.

At a time when insect populations have plummeted by 45% globally over the past 40 years, and most bird populations in India are on the decline, the Siang expedition’s findings are important. “During the Siang expedition and in subsequent visits, we’ve recorded around 400 different species of birds,” said Goswami, adding, “For perspective, the state of Meghalaya has 600 birds. India’s total bird population is something like 1,300. Around 30% of the country’s bird population can be found in this single valley.”

Botanist Ganesan R. examines a rare relative of the rafflesia, Sapria himalaya. Image by Sandesh Kadur/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

Botanist Ganesan R. examines a rare relative of the rafflesia, Sapria himalaya. Image by Sandesh Kadur/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

A threatened landscape

Arunachal Pradesh is the least densely populated state in India, with just 17 people per square kilometre, according to the 2011 census. Despite its small population, changes in land use and large development projects could permanently alter the Siang landscape.

Historically, these regions have practiced jhum (shifting) cultivation, particularly in higher elevations. Since the 1970s, the state government introduced schemes to discourage jhum in favour of settled cultivation. Schemes such as the Jhum Control Scheme and the centrally-sponsored Technology Mission on Agriculture and National Horticulture Missions also encouraged home gardens and the cultivation of fruits, aromatics, flowers, and vegetables. Settled cultivation tripled in area between the 1970s and 1990s, according to an agriculture survey.

While paddy cultivation is common along the banks of the river, mixed cultivation and orchards with fruits like orange are increasingly common on the hillslopes. The biennial Indian State of Forest Report also shows considerable deforestation in the districts along the Siang river. In 2019, the districts of East, West, and Upper Siang saw a combined deforestation rate of 75% compared to 2017. Between 2021 and 2023, forest loss in East Siang, Lower Siang, and West Siang decreased by another 32% , while Upper Siang district saw a growth in forest cover by 2.45% over the same period.

“The biggest threat right now is the disappearance of habitat,” said Goswami. “As long as habitat is there, animals can recover from other threats like hunting, because population density is relatively much lower in Arunachal Pradesh. If habitats are not converted to cash crop, agriculture or big infrastructure projects, animals and other species can still bounce back.”

A Siang mud eel (Ophichthys hodgarti). Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

A Siang mud eel (Ophichthys hodgarti). Image by Nilanjan Mukherjee/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

Another looming threat over the landscape is the 11,200-megawatt (MW) Upper Siang Multipurpose Project, a dam whose construction would sink the district headquarter of Yingkiong and alter the river’s flow dynamics forever. An outdated cumulative impact assessment of 44 proposed dams along the Siang river said silt trapped in the reservoirs of dams would “deprive the downstream Siang river ecosystem of maintenance materials and nutrients that help in maintaining the productivity of Siang and Siyom river ecosystems.”

Populations of important migratory fish species like the golden mahseer – an endangered fish with a golden hue that can grow up to 2.74 meters in size – are at risk of depleting considerably, according to the cumulative impact assessment. The golden mahseer swims upstream along Siang river in April and May, and uses the river’s tributaries for breeding, feeding and as refuge location.

Emerging community conserved areas

In the face of the anthropogenic pressures facing the Siang valley, residents of Gobuk in Upper Siang district are trying to forge a path ahead. Since 2022, an NGO led by residents of the village, Epum Sirum Welfare Society (ESWS), along with Titli Trust, are creating a model of community-based conservation to safeguard the area’s wildlife.

In the 1912 expedition, several rare species of butterflies were recorded, including one called the dark freak (Calinaga aborica) in 1915 – an endemic butterfly with brown and white patterned wings and a red body. For a century this species hadn’t been seen anywhere, save for one chance sighting made by Sondhi of Titli Trust in 2015, in western Arunachal Pradesh.

Since the 1912 expedition, the dark freak butterfly (Calinaga aborica) had evaded the eye until a chance sighting by Sanjay Sondhi of Titli Trust in 2015, in western Arunachal Pradesh. However, unbeknownst to them, Gobuk residents could find them in their backyards. Image by Sandesh Kadur/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

Since the 1912 expedition, the dark freak butterfly (Calinaga aborica) had evaded the eye until a chance sighting by Sanjay Sondhi of Titli Trust in 2015, in western Arunachal Pradesh. However, unbeknownst to them, Gobuk residents could find them in their backyards. Image by Sandesh Kadur/Felis Images (CC BY-ND 4.0).

Unbeknownst to them, the residents of Gobuk had been living among hundreds of dark freak butterflies in their backyards. “Before we learned about how rare these butterflies were, we never really paid attention,” said Anand Tekseng, a resident of Gobuk and member of the ESWS, where he works as a river guide. The residents were made aware of the value of these butterflies – and the other wildlife in the area – through workshops with Sondhi. “In 2022, we were looking for opportunities to start a community conserved area project. When we reached Gobuk, we realised the Epum Sirum had been engaged with similar work and were looking for more support. They’ve been fantastic partners,” Sondhi said.

The Adi are a hunting tribe, where rituals are considered incomplete without game. But over a span of two and a half years, residents say hunting has reduced considerably. “We used to hunt widely, whether it was squirrels, bear, deer, or birds,” said Dengwan Miyo, another resident who isn’t a member of the NGO. “We only hunt for a few festivals now. Many people have given up. It’s become a matter of pride for us that people come from so far away to see what our village has,” he said.

The dark freak (Calinaga aborica) is now a flagship of the village, and residents are building opportunities for ecotourism around the sightings of this species and the dozens of others that are found there, like the red lacewing (Cethosia biblis), blue peacock (Papilio arcturus), and the great nawab (Polyura eudamippus).

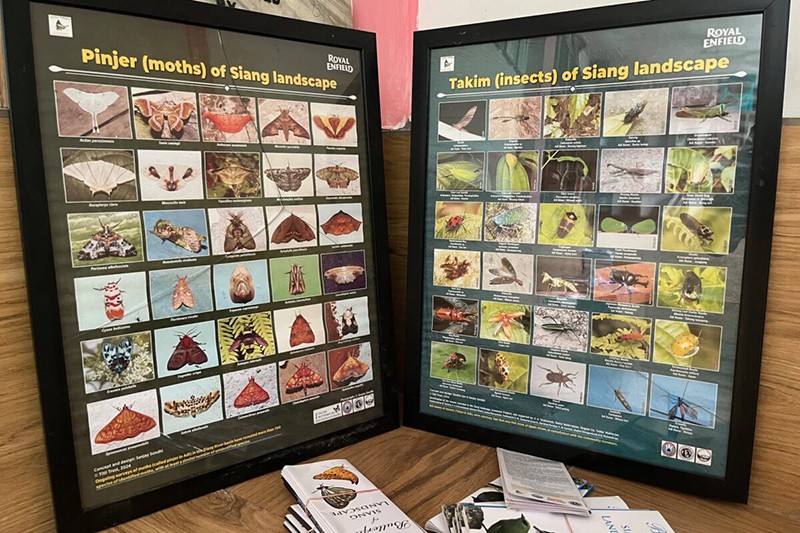

With support from Royal Enfield, Gobuk hosted its first Biodiversity Meet last year, earning around Rs. 10 lakhs from paying guests who travelled to the village and stayed in newly set up homestays to see the butterflies. Gobuk was praised by chief minister Pema Khandu for its approach to conservation. Pamphlets with photos of moths and butterflies – taken by residents and Titli Trust together – were distributed to visitors and installed in the village’s library.

Information compiled by local residents and Titli Trust on moths, butterflies and insects are on display at the Gobuk village library. Image by Hagen Desa/Mongabay.

Information compiled by local residents and Titli Trust on moths, butterflies and insects are on display at the Gobuk village library. Image by Hagen Desa/Mongabay.

Near Mouling National Park in Upper Siang, ATREE too is collaborating with villages to build community-led conservation areas. The Park is located deep in the Upper Siang district without an all-weather road, cutting the area off during the monsoons. “What we’re aiming to do is actually prevent future biodiversity loss once the area becomes better connected,” Rajkamal said. Researchers from ATREE are encouraging villages near the Park to work with the understaffed forest department and patrol the Park’s borders and foster a sense of ownership over its natural resources.

“The jury is still out on whether community-conserved areas are effective, because there are so few in Arunachal Pradesh,” said Sondhi. “But what are the alternatives? Handing land over to the government, whose forest departments are understaffed, isn’t always effective. Large infrastructure projects end up hurting communities the most. We’re still learning so much about the Siang landscape. What better way forward than to empower communities to participate in this learning too?”

Mongabay India/TWF

IBNS

Senior Staff Reporter at Northeast Herald, covering news from Tripura and Northeast India.

Related Articles

Ozone hole recovery accelerates: 2025 size among lowest in decades, NASA reports

While continental in scale, the ozone hole over the Antarctic was small in 2025 compared to previous years and remains on track to recover later this century, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported.

Delhi orders 50% office attendance as toxic air triggers GRAP-3

Delhi’s worsening air pollution has pushed the city into GRAP-3, prompting the government and private offices to operate with only 50 percent staff on-site, while the rest work from home.

Malaria vaccine just got cheaper! Gavi and UNICEF slash prices in major deal

COP30 in Belém delivers huge climate finance push

In a pivotal outcome at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, countries agreed on a sweeping package to scale up climate finance and accelerate implementation of the Paris Agreement – but without a clear commitment to move away from fossil fuels.

Latest News

'Kill India' chants, flags desecration, at Ottawa Khalistan referendum amid Modi-Carney G20 talk

Tripura supplies power for over 23 hours daily: Power Minister

Australian senator suspended for rest of year after wearing Burqa in Parliament protest

Poll shock for Sadiq Khan: Labour slumps, Reform UK climbs