Buddhism regained its position of prominence in 19th-20th centuries India: New Book

Buddhism, which went through a process of decline in the 13th century, regained the centre stage of Indian outlook, history, panorama and international relations especially in the 20th century through its role in diplomacy, identity politics, refugee issues, social emancipation and political movements, claims a newly launched book.

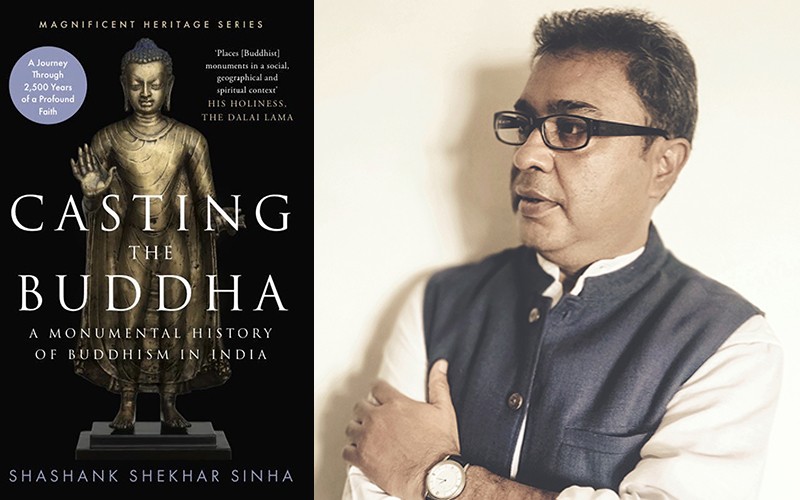

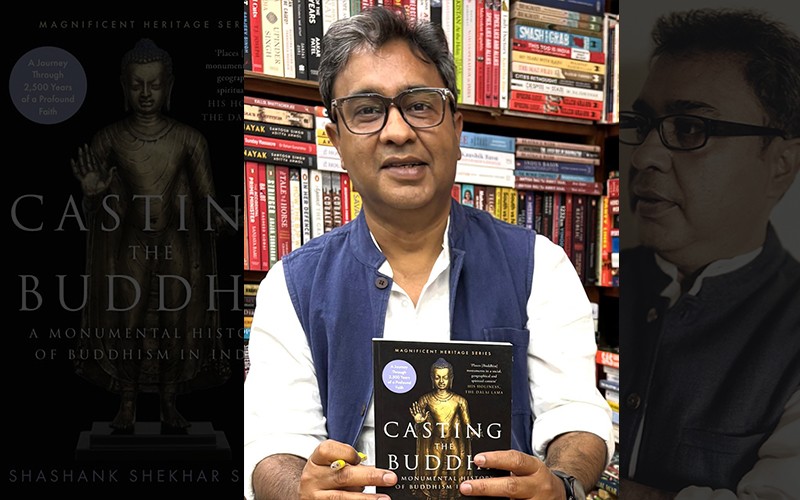

In his latest book, "Casting the Buddha: A Monumental History of Buddhism in India", veteran author and historian Shashank Shekhar Sinha argues that one needs to go beyond the traditional frames of looking at decline of Buddhism in terms of Brahmanical revival, permeation of tantrism, and iconoclastic Indian Muslim rulers in the 13th century, and look at reasons of dwindling support and patronage, changing role of the monks, and regional complexities too.

Challenging the widely accepted theory that Buddhism vanished from its birthplace India in the 13th century, Sinha writes that Buddhism continued to thrive in places like Lahaul and Spiti and Bengal and Indians continued to talk about the Buddha and his dharma even after the faith was declared “dead” in India.

Buddhism remained a subject of public conversations in India. Buddha continued to figure in oral traditions, popular literary works, hagiographies, commentaries, and collective memory alongside the Puranas which portrayed him as an avatar or incarnation of Vishnu, a Hindu God.

Undoubtedly, the story of how Buddhism set down its roots in India is enshrined within ancient stupas, temples, monasteries and caves, though it came into limelight of Indian politics in modern India through the mobilization of the depressed or marginalized castes.

In the Nehruvian-era, this enduring faith became an important tool in forging ties with Buddhist countries in South, Southeast and East Asia. Successive Indian governments since Nehru have used India’s Buddhist past to establish symbiotic or civilizational links with many countries of East, Southeast and South Asia including Sri Lanka and Myanmar, says the book.

Speaking with India Blooms, Sinha explains Casting The Buddha is primarily about Buddhist monuments and archaeological remains in India and their relationship with Buddhist texts of the day. He advises students of Buddhism to correlate what they read in the texts with what they see in the monuments and artefacts in order to better understand and accurately portray the beliefs, practices and culture that prevailed during the “Buddhist-era” in India.

Archaeological remains, he cautions, sometimes tell a story different from the texts. Further, monuments and artefacts need to be studied through more dynamic and inclusive frameworks which, Sinha underscores, go beyond art and architecture to include the site’s afterlife, its larger-geo-cultural connections, the relationship between the individual structures/artefacts and the monument complex, the role of humans and human-led agencies, and the wider ecological settings.

The author notes that the Europeans rediscovered Buddhism in the 19th century and helped spread an awareness of it across the West. However, the advent of archaeology, print culture, and English education during the colonial period contributed to an increase in the knowledge of Buddhism in India, and its repositioning.

Casting The Buddha presents an illustrated history of Buddhist monuments in India, spanning 2,500 years. It explores tangible representations of the Buddha and artefacts related to him such as sculptures, images, votive stupas, paintings, tablets, miniature images, shrines and steles (Buddhist stone tablets).

The stupa remains need to be correlated with contents in the written texts to get a full picture of the ideas and practices of Buddhism in various places. The sculptures give evidence of Buddhist practices. Coins, inscriptions and artefacts help us tell the story with greater accuracy; Sinha elaborates.

The book highlights that the evolution of Buddhism was not just limited to developments within the Buddhist faith, but also in Hinduism, Jainism, popular cults and other rudimentary and ascetic traditions.

Hindu reform movements like Brahmo Samaj and Prarthana Samaj also helped create an interest in Buddhism. Buddhist societies were formed in many parts of India and these societies produced Buddhist literature. Tagore included Buddhist themes in his artistic productions.

Even the Hindu Mahasabha patronized Buddhism though it maintained that Buddhism was only “reformed Hinduism” and not a separate religion. Hindu business houses also supported and propagated Buddhism, the historian discloses.

Buddhism also inspired anti-caste movements, and efforts to build an egalitarian society through the Constitution of independent India. After independence, Buddhism was grafted into state craft, nation building and international relations too.

Historian Shashank Shekhar Sinha argues in his book that one needs to go beyond the traditional frames of looking at decline of Buddhism

Historian Shashank Shekhar Sinha argues in his book that one needs to go beyond the traditional frames of looking at decline of Buddhism

Even today, politicians use Buddhism to promote egalitarian ideas. Even orthodox believers in caste are co-opting Buddhism to interpret Brahminical Hinduism as containing within itself the Buddhist idea of a caste-free society.

Interestingly, the chapter titled ‘Buddhism 2.O’ discusses how Buddhist monuments gained visibility for reasons beyond religion – soft power diplomacy, identity politics, refugee and diaspora issues, tourism and heritage conservation – and how these factors imparted new meanings and forms to both the monuments and Buddhism.

Across three sections and eleven chapters, Casting the Buddha charts the remarkable and monumental journey of a faith that began during the 6th and 5th centuries BCE and infuses new life into a timeless faith.